A Primer on Proudhon and Property

Mutualism is the middle path and reconciliation of capitalism and communism

Proudhon's take on "property" is a brilliant kaleidoscope, full of different views that all come from the many ways people justify it. His ideas on collective ownership of the land and the natural resources are distinct from his thoughts on collective ownership of "capital"—the tools we use to get work done, or academically termed as the instruments of labour.

The first idea springs from the simple truth that nobody “produced” the land and the natural resources — it was all here before us. But the second idea comes from his own game-changing theory about collective force, most specifically on how we can do so much more when we pool our efforts together.

TL:DR — property in capital and land is indivisible, and consequently inalienable

Proudhon was clear-cut about it: nobody has the right to stick a flag in the ground and say, "This land and these natural resources—they're mine!" After all, no human made them. Their value is shared, kind of like a big potluck dinner provided by Nature for all of us to enjoy. Driven by this belief, Proudhon put forward the idea that the land and natural resources should belong to everyone, used by each person separately, analogous to borrowing a book from a public library. And this system, which he termed as Mutualism Usufruct, would be safeguarded by something he called a "free contract."

Proudhon's concept of "collective force" is like a powerful spotlight, showing us the unfairness hidden within how things are produced and why it's essential for "capital" (the means of production) to be collectively owned. Proudhon starts with the idea that if you work to make something, it should be yours. He then takes a good hard look at how things can go wrong in the production process and decides that the tools and machinery we use to make things should be like the land and natural resources — owned by everyone and not divided up.

Why? Because Proudhon saw that when we work together, we can create more than if each of us were doing our own thing. "Collective force" was Proudhon's rallying cry against the notion of few people owning the means of production. When the capital is owned by everyone, workers turn from wage-earners into partners. They clock in at the workplace and get to enjoy the full fruits of their labor. So, any extra value or profits we create should go to everyone, not just the person who owns the tools or machinery.

Proudhon had a bone to pick with "communism". In his view, a member in a community(ism) didn't own anything personally, but the community as a whole owned everything. And by everything, Proudhon meant not just goods, but also people’s desires and their willpower. That meant workers did not control their own labour nor its product (goods). Proudhon was fired up against this definition of "community(ism)" as he called it. He despised top-down entities owning all the "capital" or calling all the shots in the economy and society. Proudhon was always making a case for diffusing the power around.

In capitalism, ownership and use are divided, while in communism, they are undivided. Now, enter Proudhon's idea of Mutualism. It's not "communism" or "capitalism", but more like a peace treaty between the two. A synthesis of the two meant that ownership had to be undivided while use was divided. A recipe where everyone shares ownership, but usage is divided up. It's a system that wraps its arms around the entire society, but still lets each person keep their rights and the freedom to do their own thing.

Capitalist businesses and communist unions can sometimes seem like exclusive clubs, only open to a set number of people, with everyone else left out in the cold. But Proudhon's idea of Mutualist Usufruct throws open the doors as an “open membership.” It leans towards being universal — it's for everyone, everywhere. And what's the result? The crowd, the everyday person, they are the ones truly in charge. Because the main economic organism—the land and capital—they belong to ‘the people’ as each person.

But here's the thing: to put an end to exploitation, things like land, natural resources, and "capital" should be collectively owned by the people. But we also need to divide up who uses what, to keep the paradox of freedom alive. Most get mixed up between these two—using something (which is divided up) and owning it (which isn't). Proudhon’s position on land use is best described as Mutualism Usufruct, or private use of common property, rather than a type of exclusive private property.

In a nutshell

Proudhon championed the idea of land and capital being socially owned—or as he put it, 'indivise', meaning undivided or shared or partial common ownership. This partial common ownership creates the backdrop for individual possession (the right to use). So, while the community as a whole owns the property, the right to use it is given to individuals or groups, bonded by a 'free contract'. And although the tools and means for production should be public, it's the workers themselves who should steer the production process.

Thought Experiment: A Post-Capitalist Mutualism Usufruct For Land

Envision an island — like Sri Lanka — where the entire geographical terrain is in a perpetual state of auction. Picture each parcel of land with a bidding price and anyone placing a higher bid than the existing rate gains ownership. A significant portion of 0ASIS is dedicated to the exploration of such a Post-Capitalist Mutual Usufruct system.

Considering that every individual globally has equal rights to land and natural resources — under the witness of geoautonomy — these rights are not perpetual ownership rights but rather a right to use or possess, or "Mutualism Usufruct." There are multiple forms these equal rights can take, with the main one being the generation of a competitive usage market through partial common ownership. Partial Common Ownership, also known as Self-Assessed Licenses Sold Via Auction (SALSA), presents a novel, fairer and efficient method of land management compared to capitalism or communism.

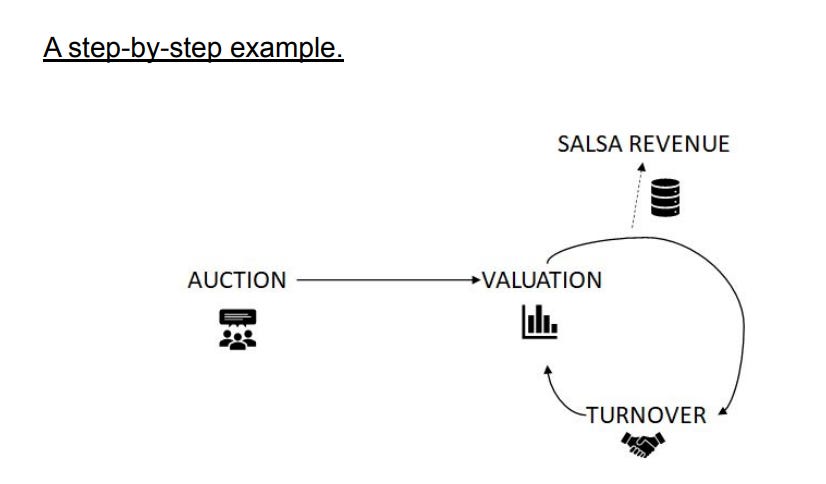

In SALSA systems, land belong to no one and everyone. The current possessor of the plot of land, must self-assess and declare its value. Based on the self-assessed value, they pay a fee, which can be used to fund public goods, or distributed as a social dividend as basic income. If somebody bids more for that plot of land, current possessors sell it for their self-assessed value, resulting in more benefits for the public.

Step 1. Sell a set number of licenses. We recommend using a Dutch auction (i.e., descending price) or a Channel auction. (In a Channel auction, there is a lower bound price, which gradually rises, and an upper bound price, which gradually descends. Buyers are committed to buy, for at least the lower bound price, but may purchase directly at the upper bound price at any time.)

Step 2. Holders post their self-assessed valuations in an online platform and pay annual fees on them (e.g., a 20% fee). As mentioned above, the right annual fee rate will be somewhere between zero and the turnover rate (i.e., the probability that a higher-value pur- chaser comes along within a year).

Step 3. Purchasers who value the asset higher may buy it at any time in the online marketplace.

As part of this thought experiment, let's assume that the SALSA auctions are facilitated through smartphone apps that automatically place bids based on preset settings, negating the need for constant bid calculation. Regulations are in place to prevent potential disruptions (like unexpectedly losing ownership of your residence). Incentives are provided to foster land care and development, and to maintain privacy or other values. All auction revenue would be distributed evenly among citizens as a "Basic Income Grant" or used for public initiatives.

This SALSA auctioning would revolutionise Sri Lanka’s societal and political landscape. Firstly, people's perception of their land would shift. The clear demarcation between owning a house and occupying a beach spot would fade. Private land would become public to a significant extent and the possessions of those around you would, in a sense, become partly yours.

Secondly, the constant auctioning typical of a SALSA market would rectify the extensive misuse of lands and other resources. The highest bidder for picturesque hillsides would never be someone planning to erect shaky, rundown slums. Central city land's highest bidders would be the constructors of upscale condos or skyscraper builders for the emerging, middle class generated by the auction.

A third consequence would be the eradication of the main cause of wealth disparity. While one may initially presume that the auction would enable the wealthy to monopolize all valuable assets, reconsider — what defines wealth?People who own lots of land, and so forth. But if all plots of land were up for auction all the time, no person would own such land, their benefits would flow equally to all.

Fourthly, the Sri Lankan SALSA would curtail corruption by shifting key political decisions from politicians to the citizens. Instead of the conventional image of "free" markets catering to and eroding the public sphere, such Wild Markets (SALSA) would enhance trust in public affairs.

Fifth, if all land in Sri Lanka were collectively funded and liberated, it could produce a “Basic Income” of over $10,000 annually for each person under the “Witness” of Geoautonomy. GDP would become irrelevant; grassroots, localized spending would significantly enhance purchasing power, proving far more effective than top-down “GDP” economics.